Volvo 850 Estate BTCC Prototype

Posted by Scott in Uncategorized, tags: 5 cyl, 850, BTCC, Estate, Super touring, Volvo, WagonVolvo 850 Estate If the BTCC championship was decided by the amount of press coverage an individual car received over a season, then the Volvo 850 Estate would have won the title before it ever turned a wheel. For many, the idea of racing an estate car was laughable but for Volvo it would provide them with the level of media exposure they were looking for. Most thought that the estate model was purely a sales gimmick dreamt up by the clever marketing team within Volvo, but BTCC folklore suggests that the estate concept did not originate within Volvo but rather as the result of a chance circumstance during the early stages of the 850 project. In 1992, Volvo Senior Vice President Martin Rybeck looked at improving the image of Volvo cars by returning the marque back to motorsport, which they had quit in 1987.

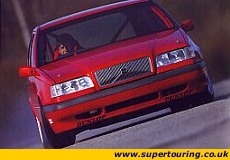

He decided that the BTCC was the obvious place to launch a return but his fellow board members needed convincing that the rather large 850 was up to the job. Rybeck therefore commissioned a prototype 850 to be built by long term Volvo specialist Steffanson Automotive (SAM) to prove it could be turned into a competitive race car. Volvo provided SAM with suitable technical resources and asked them to collect an engine and bodyshell on which to base their prototype. However, the day SAM came to collect them from the factory only estates were being built, so rather than delay the start of the project they decided to use the estate bodyshell instead. When Rybeck heard what had happened he immediately realised that the marketing potential for racing an estate would be massive, but he was keen to ensure that racing the estate would not be a failure compared to the saloon version.

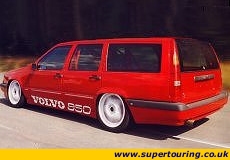

To satisfy his doubts, Rybeck first tested both body types in Volvo’s own wind tunnel in Gothenberg. The results showed that there was little difference between the two body shapes, and in fact the estate offered better downforce over the saloon due to it’s long flat roof.

Rybeck also brought in motorsport experts Tom Walkinshaw Racing (TWR) to evaluate the estate as a potential racer. TWR, who had been Volvo’s on track rival when it raced in the European championship during the 80s, confirmed that so long as the weight could be brought down to the legal minimum, there was unlikely to be much difference between the two cars on the circuit.

Volvo confirmed its intent to join BTCC towards the end of 1993, and showed both saloon and estate racers at the Swedish Motor Show the following January. This generated enormous media speculation until Volvo finally came clean and announced at the Geneva Motorshow a month or so later that they would actually be racing the estate.

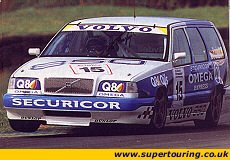

Although the decision to run the estate was taken quite early on, the go ahead to build the race cars was not given till extremely late in 1993. The 3 year contract to run the cars was given to TWR, who struggled to get them ready for the first race of the season. In fact the first full race car did not turn a wheel until the first test session at Snetterton on the 4th April, a mere seven days before the first race of the season.

Unlike the red test car, the race cars were designed by TWR at their Oxfordshire base, the original design work performed by Richard Owen, the same man who penned the Jaguar XJ220 for TWR back in late 80s.

Although new to Super Touring racing, TWR has a vast experience in touring car racing and other forms of motorsport and they used much of this knowledge when designing the 850 in an attempt to make the car competitive.

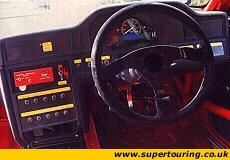

The first idea was within the engine bay, which was to house the chosen 5 cylinder, DOHC 20 value engine. When TWR first looked at the the Volvo, they realised that the weight distribution of a front wheel drive car was extremely important. They also realised that by moving some of the weight from over the front wheels that they could improve the balance of the car on the track.

So TWR designed a special gearbox and subframe which allowed the engine to be lowered and moved back within the engine bay so that the weight of the engine was behind the front axle line. Luckily there was plenty of space under the bonnet of the Volvo as a result of having to fit turbo chargers to some of the road-going models, and so TWR used that to their advantage.

The weight distribution within the cabin was also looked at closely, and TWR decided to move the driver’s seating position as close to the center of the car and as low down as possible within the rules. This places the driver almost parallel to the central door pillar, controlling the car through an extended steering column and pedals.

With two designs in place, the Volvo was able to run close to a 50/50 weight distribution, which when coupled with the car’s extremely wide track should have made it’s cornering ability second to none. Unfortunately, what TWR found was that the car performed badly through slow corners as a lack of direct weight over the front axle caused the front wheels to loose grip, but through fast corners the car performed extremely well.

Although the Volvos did not perform miracles in their first season, they did make great improvements in their performance and TWR would be the first to admit that it was a steep learning curve for all concerned. The cars did suffer from having an extreemly large frontal area, being very wide, but an extreemly strong engine made up for this

In 1995 the introduction of wings made the estate no longer viable as a race car and the team swapped to the 850 saloon instead.

Entries (RSS)

Entries (RSS)